Jewelry designed by Salvador Dali is the hot ticket these days at auction and museums. Three major exhibits are spotlighting the jeweled versions of his surrealism this year.

Jewelry designed by Salvador Dali is the hot ticket these days at auction and museums. Three major exhibits are spotlighting the jeweled versions of his surrealism this year.“My art encompasses physics, mathematics, architecture, nuclear science – the psycho-nuclear, the mystico-nuclear – and jewelry – not paint alone,” Dali wrote in the 1959 catalog Dalí: A Study of his Art-in-Jewels. “My jewels are a protest against emphasis upon the cost of the materials of jewelry.

“My object is to show the jeweler’s art in true perspective – where the design and craftsmanship are to be valued above the material worth of the gems, as in Renaissance times.”

Dali had everything to do with the design but little to do with the craftsmanship of his jewels. Like most Modern artists who experimented with jewelry, he relied on others for that – specifically, New York goldsmith Carlos Alemany. (Alexander Calder was a notable exception, making all his jewelry by hand.)

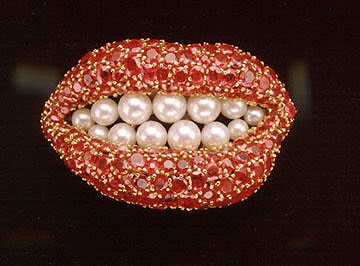

But Dali personally selected the stones: rubies to represent energy, sapphires tranquility and lapis lazuli the subconscious mind. His early attempts produced striking, bejeweled translations of his surrealist paintings: hearts bursting open and dripping blood, eyes weeping and melting, sensuous lips.

Eye of Time brooch. "Man cannot escape or change his time. The eye sees the present and the future." -Dali

Dalí was a prolific jewelry designer by the time that 1959 catalog was published for the Owen Cheatham Foundation. “Though many of Dali’s jewels would also amuse the most surfeited, others startle with a note that is not common in such expensive objects, for they explode with agony,” wrote the late A. Hyatt Major, then curator of prints for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in the foreword. “Crystals pierce; rubies bleed.”

Mae West's come-hither smile inspired this 1949 brooch. "Poets of the ages, of all lands, write of ruby lips and teeth like pearls." -Dali (photo courtesy Primavera Gallery)

Schiaparelli commissioned Dali’s earliest jewelry, including his telephone ear “rings.” During this period, he designed his heart brooch dripping ruby blood and a melting-eye watch.

Dali’s fabulous mid-century jewels have always brought good prices and their value is rising as the work he produced later in his career attracts more serious attention. (Until recently, most of what Dali created after 1940 was panned by critics.) In 1995, a Dali Starfish piece with an unsigned drawing sold for $170,000 at Christies. Two years later, the Dali museum in Figueras, Spain, opened a permanent collection of his jewelry.

Among the exhibits highlighting Dali’s jewelry this year, Salvador Dalí: The Late Work opened at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta in August and runs through January 9, 2011, the first major museum exhibit devoted specifically to work the Spanish artist created after Dalí split with the Surrealists in the late 1930s.

Dali’s surrealistic jewels also appear in Jewelries by artist: From Modernisme to the avant-garde opening October 27 at Barcelona’s Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Dali’s surrealistic jewels also appear in Jewelries by artist: From Modernisme to the avant-garde opening October 27 at Barcelona’s Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.His Starfish brooch (right) was among the nine Dali jewels featured in “Surreal Things” at the Art Gallery of Ontario last summer. Each arm of the pearl, diamond, ruby and emerald pin is articulated to wrap around hand and fingers.

A signed watercolor sketch for Dali’s “Etoile de Mer” series sold at Christie’s last year for $47,500, on an estimate of $10-15,000, and a set of ruby- and diamond-encrusted bleeding heart brooch and earrings (above right) were estimated at $200,000 at Sotheby’s in 2006.

No comments:

Post a Comment