I recently took a trip to the Salvador Dalí museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. It had been a while since I’ve visited a fine art museum, so I was incredibly excited. It was also the first time that I visited the new location for the museum—I had been to the original museum about a year before they changed locations.

I vaguely remember the original museum being relatively small, so I wasn’t expecting much. So, when I pulled into the new parking lot, I thought that I may have gotten wrong directions. Upon further examination, I realized that I WAS in the right spot; the museum was about three times larger, and took advantage of being right on the water by including a large patio area for visitors to lounge on. I was immediately impressed. After a small stroll through downtown to get some food, I made my way back to the museum’s outstanding entrance.

Visitors walk on a small bridge overlooking an impressive pond filled with beautiful landscaping. Walking through the automatic doors leads the visitor through an impressive gift shop. Of course, visitors are encouraged (perhaps even forced) to traverse around the prints, mugs, calendars, and games in order to arrive at the desk where tickets are purchased.

I went on a Thursday after five, due to the fact that tickets are reduced to 10 dollars—instead of an insane 20 dollars per guest. Once a ticket is purchased, each guest receives a wristband and is guided towards an unbelievable staircase. This staircase leads directly to the gallery on the third floor, and is spiral in shape—I was immediately reminded of the spiral shells that are present in much of Dalí’s surrealist works.

Once at the top, the visitors have three options: they can either go towards the gallery of Dalí’s prints and movies, or to a “glass enigma” overlooking the Tampa Bay, or towards the main gallery that contains Dalí’s most famous works.

I went to the direction of his prints. In these prints, I examined Dalí’s incorporation of props for ambiguous limbs, melting clocks, and symbolism that is prominent in his later works. Also in this large room are some examples of Surrealist sculptures, including Venus de Milo with Drawers (Figure 1). This sculpture is one of four casts created in 1964 from the 1936 original. Another interesting sculpture was the Lobster Telephone, a work conceived two years before its execution, and is one of six copies. The Surrealist aspect of this work can be found in the fact that the functionality of the object is completely removed and the object is nothing but an object to look at. After closely inspecting these sculptures, I headed to the other side of the gallery, where an interesting work rests. This work is titled First Cylindrical Chronohologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain, and is a rainbow hologram that is visible in the round. The last interesting piece in this room is a separate section in which guests can view various short films created by students at local high schools. I watched a few of these films and then headed to the main gallery.

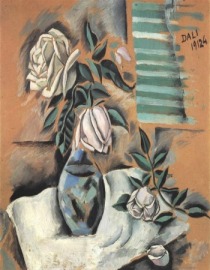

Before officially entering the gallery, I read the place cards that explained who Dalí was, the basic premise of his life, and the patrons who made it possible for the museum to exist. On these place cards, I learned that Dalí officially broke from the Surrealist movement in 1939, and began to work through other genres. Entering the room brings visitors to his works in chronological order, beginning with works created in school and soon after. Very much surprising to me was the fact that his earliest works are very close in style to the Post-Impressionist works of Monet and Manet. These works contain an unbelievably thick application of paint and traditional subject matter. The 1920s brought more Realism for Dalí, including Bouquet (Figure 2), a painting done in the traditional mode and medium in 1924. With Femme Couchée (1926), I noticed faint undertones of Cubism. With the 1925 Study of a Nude, Dalí’s canvas becomes more visible as he heads back to the principles of Post-Impressionistic works. The first work in the museum the visitor sees that is distinctly Surrealistic in style is Portrait of My Dead Brother (Figure 3), painted in 1963. This painting contains scientific DNA-like sequencing that is present in other works.

After viewing this work, the visitor is guided to a section containing Dalí’s works from his “Non-Art Period”. I had never heard of this period before, so I was incredibly interested. This period was Dalí’s reaction against the Academy and contained rebellious works such as The Bather, and The Yellow Manifesto. In Manifesto, I noticed Dalí’s inclusion of amorphic forms that I had seen previously in his prints. As I traveled more into the gallery, I noticed Morphological Ego, painted in 1934. This painting strongly reminded me of the Metaphysical School prominent in the early 1900s. This school of thought was characterized by Surrealist forms such as shadows, empty spaces, and people placed in odd places. In Dalí’s experimentation of this style, women in the right corner with shadows fit the description of this school. The first massive Dalí work that I noticed was The Discovery of America by Christopher Colombus (Figure 4). Since I consider myself a formalist, I will analyze the works from a formalist perspective, but I ask readers to keep in mind that Dalí’s works in this time period are flowing with symbolism and

require a much further thorough investigation to truly understand. The first thing that I noticed in this work is that Dalí incorporated different hues of primary colors. The composition is mainly vertical, but also contains a hint of a triangular composition; since this work has a high level of religious imagery, it is fitting that Dalí would include a Holy Trinity composition. He also incorporated pointillism on the right side of the painting, creating a sense of asymmetrical balance.

After sitting and looking at this work for twenty minutes, I headed to a almost hidden room containing Dalí’s pencil drawings, and I was very impressed. One of my favorite aspects of visiting a fine art museum to analyze is the presence of the artist, and these drawings put me in heaven—I could even see where Dalí had erased his lines and redrew them! Christ in Perspective (1950) was erased and redrawn many, many times.

My absolute favorite Dalí painting is The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1969; Figure 5), and I definitely stare at it in awe every

time I see it. Interestingly, Dalí found influence for this painting not through hallucinogenic drugs—he claims to never have used them—but through his realization that he lacked art supplies! He went to his local art store and found a pack of supplies with the Venus de Milo on the cover, and found his inspiration in that. This work contains an insanely bright use of color, and the Venus actually works to balance out the composition. This painting contains religious imagery, and for fun, hidden gems! For instance, when viewed in a different light, one can see that Dalí incorporated a illusionistic self-portrait. Also present in this painting is a superimposition of images which could possibly confuse the viewer. Overall, this work is my favorite Dalí work, and I love seeing it in person.

To analyze Dalí’s works as a whole from a formalist perspective, I feel that there may be something lacking. Dalí primarily focused on the symbolism within his works, and thus focused less on formalist aspects. In my personal opinion, I highly respect Salvador Dalí and his contributions to the art world. Some principles of art may be missing in a number of his works, but I feel that his experimentation within his field makes him quite the respectable artist.

I highly recommend visiting The Dalí Museum for yourself and viewing the works up close. For more information, please visit the Dalí website or call them at (727)823-3767.

I vaguely remember the original museum being relatively small, so I wasn’t expecting much. So, when I pulled into the new parking lot, I thought that I may have gotten wrong directions. Upon further examination, I realized that I WAS in the right spot; the museum was about three times larger, and took advantage of being right on the water by including a large patio area for visitors to lounge on. I was immediately impressed. After a small stroll through downtown to get some food, I made my way back to the museum’s outstanding entrance.

Visitors walk on a small bridge overlooking an impressive pond filled with beautiful landscaping. Walking through the automatic doors leads the visitor through an impressive gift shop. Of course, visitors are encouraged (perhaps even forced) to traverse around the prints, mugs, calendars, and games in order to arrive at the desk where tickets are purchased.

I went on a Thursday after five, due to the fact that tickets are reduced to 10 dollars—instead of an insane 20 dollars per guest. Once a ticket is purchased, each guest receives a wristband and is guided towards an unbelievable staircase. This staircase leads directly to the gallery on the third floor, and is spiral in shape—I was immediately reminded of the spiral shells that are present in much of Dalí’s surrealist works.

Once at the top, the visitors have three options: they can either go towards the gallery of Dalí’s prints and movies, or to a “glass enigma” overlooking the Tampa Bay, or towards the main gallery that contains Dalí’s most famous works.

I went to the direction of his prints. In these prints, I examined Dalí’s incorporation of props for ambiguous limbs, melting clocks, and symbolism that is prominent in his later works. Also in this large room are some examples of Surrealist sculptures, including Venus de Milo with Drawers (Figure 1). This sculpture is one of four casts created in 1964 from the 1936 original. Another interesting sculpture was the Lobster Telephone, a work conceived two years before its execution, and is one of six copies. The Surrealist aspect of this work can be found in the fact that the functionality of the object is completely removed and the object is nothing but an object to look at. After closely inspecting these sculptures, I headed to the other side of the gallery, where an interesting work rests. This work is titled First Cylindrical Chronohologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain, and is a rainbow hologram that is visible in the round. The last interesting piece in this room is a separate section in which guests can view various short films created by students at local high schools. I watched a few of these films and then headed to the main gallery.

Before officially entering the gallery, I read the place cards that explained who Dalí was, the basic premise of his life, and the patrons who made it possible for the museum to exist. On these place cards, I learned that Dalí officially broke from the Surrealist movement in 1939, and began to work through other genres. Entering the room brings visitors to his works in chronological order, beginning with works created in school and soon after. Very much surprising to me was the fact that his earliest works are very close in style to the Post-Impressionist works of Monet and Manet. These works contain an unbelievably thick application of paint and traditional subject matter. The 1920s brought more Realism for Dalí, including Bouquet (Figure 2), a painting done in the traditional mode and medium in 1924. With Femme Couchée (1926), I noticed faint undertones of Cubism. With the 1925 Study of a Nude, Dalí’s canvas becomes more visible as he heads back to the principles of Post-Impressionistic works. The first work in the museum the visitor sees that is distinctly Surrealistic in style is Portrait of My Dead Brother (Figure 3), painted in 1963. This painting contains scientific DNA-like sequencing that is present in other works.

After viewing this work, the visitor is guided to a section containing Dalí’s works from his “Non-Art Period”. I had never heard of this period before, so I was incredibly interested. This period was Dalí’s reaction against the Academy and contained rebellious works such as The Bather, and The Yellow Manifesto. In Manifesto, I noticed Dalí’s inclusion of amorphic forms that I had seen previously in his prints. As I traveled more into the gallery, I noticed Morphological Ego, painted in 1934. This painting strongly reminded me of the Metaphysical School prominent in the early 1900s. This school of thought was characterized by Surrealist forms such as shadows, empty spaces, and people placed in odd places. In Dalí’s experimentation of this style, women in the right corner with shadows fit the description of this school. The first massive Dalí work that I noticed was The Discovery of America by Christopher Colombus (Figure 4). Since I consider myself a formalist, I will analyze the works from a formalist perspective, but I ask readers to keep in mind that Dalí’s works in this time period are flowing with symbolism and

require a much further thorough investigation to truly understand. The first thing that I noticed in this work is that Dalí incorporated different hues of primary colors. The composition is mainly vertical, but also contains a hint of a triangular composition; since this work has a high level of religious imagery, it is fitting that Dalí would include a Holy Trinity composition. He also incorporated pointillism on the right side of the painting, creating a sense of asymmetrical balance.

After sitting and looking at this work for twenty minutes, I headed to a almost hidden room containing Dalí’s pencil drawings, and I was very impressed. One of my favorite aspects of visiting a fine art museum to analyze is the presence of the artist, and these drawings put me in heaven—I could even see where Dalí had erased his lines and redrew them! Christ in Perspective (1950) was erased and redrawn many, many times.

My absolute favorite Dalí painting is The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1969; Figure 5), and I definitely stare at it in awe every

time I see it. Interestingly, Dalí found influence for this painting not through hallucinogenic drugs—he claims to never have used them—but through his realization that he lacked art supplies! He went to his local art store and found a pack of supplies with the Venus de Milo on the cover, and found his inspiration in that. This work contains an insanely bright use of color, and the Venus actually works to balance out the composition. This painting contains religious imagery, and for fun, hidden gems! For instance, when viewed in a different light, one can see that Dalí incorporated a illusionistic self-portrait. Also present in this painting is a superimposition of images which could possibly confuse the viewer. Overall, this work is my favorite Dalí work, and I love seeing it in person.

To analyze Dalí’s works as a whole from a formalist perspective, I feel that there may be something lacking. Dalí primarily focused on the symbolism within his works, and thus focused less on formalist aspects. In my personal opinion, I highly respect Salvador Dalí and his contributions to the art world. Some principles of art may be missing in a number of his works, but I feel that his experimentation within his field makes him quite the respectable artist.

I highly recommend visiting The Dalí Museum for yourself and viewing the works up close. For more information, please visit the Dalí website or call them at (727)823-3767.

No comments:

Post a Comment